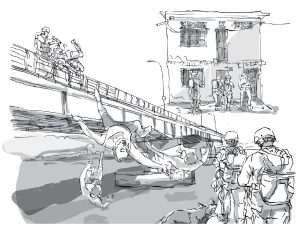

The declaration of an internal armed conflict in the country, the displacement of the violence towards popular urban neighborhoods and rural territories, the dramatic increase of socioenvironmental conflicts in peasant, indigenous and afroecuadorian communities.

The document can be downloaded here.

1. Introduction

More than six months after the declaration of an internal armed conflict and the approval of an state of exception in seven provinces of the country, the Observatory of Territorial Conflicts of Ecuador (OCTE) presents a report that synthesizes the violation of human rights in the country from January 9 to July 31, 2024. The report was prepared using an inductive methodology that incorporates testimonies from several sectors and spaces of Ecuador.

2. Some quantitative findings

Primary data coming from the places in which the OCTE realizes its activities was used in the elaboration of the report. This methodological choice prioritized trust relations with our territorial partners. We also gave priority to a deep understanding of the cases reported. This document, consequently, does not pretend to show systematic quantitative patterns that represent the overall country. Rather, it gives us an accurate vision of some of the forms through which the violence in Ecuador takes form in the current context.

The report contains the information of 28 cases collected in 8 provinces: 3 in the coast (Esmeraldas, Manabí and El Oro), one in the southern amazonia (Morona Santiago) and 4 in the highlands (Imbabura, Pichincha, Cotopaxi, Bolívar). Esmeraldas, not surprisingly, is the province that gathers the biggest number of cases of human rights violation, 14 in total. There are two main indigenous nationalities affected by the current context of violence in Ecuador, the Shuar -of the southern part of the amazonia- and the Chachi -of the Esmeraldas. In the latter province we could also register information about systematic violence conducted towards the afroecuadorian and peasant community of San Javier de Barranquilla. Likewise, peasant communities in the sierra or highland territories of Las Naves (province of Bolívar) and Las Pampas – Palo Quemado (province of Cotopaxi) suffered from violent interventions conducted by the state. These interventions aimed at imposing socio-environmental consultation processes to facilitate the operation of big mining projects that do not have public legitimacy. In both of these spaces, the state treated as terrorism any attempt of social resistance, incriminating local leaders in order to demobilize any opposition. In addition, two aggressions towards representatives of civil society organizations were also registered.

3. General Conclusions

The violence and the violation of human rights reported remind us to a famous quote of the Argentine philosopher Veronica Gago: most of the questions are repeated, they come back and insist […] they are always the same questions that come to play, under different forms, tones and velocities. The president Noboa, instrumentalizing the state of fear of the population in the beginning of 2024, applied hard measures to combat criminal gangs. These measures reconfigured the overall violence framework in Ecuador: the figure of the terrorist came into the center. This category has an enormous plasticity: from the young male involved in small drug traffic in Guayaquil to the human rights defender that disturbs the state and big extractive corporations.

During the last 7 months, the ecuadorian government has consolidated a pattern: localized state of exception, military presence in specific neighborhoods and prison control, and selected combat operations retransmitted by the main television channels. All this combined with regressive fiscal measures, like the increase of value-add and gas taxes, with the defended purpose of defraying public force mobilization. Moreover, the government has approved the removal of the tax to gun imports, with the intention to consolidate an idea of individual responsibility in the face of this structural violence.

This instrumentalization of fear is at the front of the current government strategy. In an understanding of politics as a mere act of communication, Noboa tries to show that his actions are being effective. However, official data does not match the government propaganda, constantly replicated in the media. Beyond the glorifying discourses around Noboa and his measures, it is important to remind that the growth of the criminality in the country is a direct consequence of public policy, or the lack thereof. This is paradigmatic in provinces such as Esmeraldas, where criminal groups represent for many young men the only way to make a living and have a sense of belonging.

With the public support to combat organized crime, Noboa has paved ground to advance some of the strategic extractive projects that had been stopped for years due to the social resistance they provoked. Environmental activists, human rights defenders and social organizations are subject to being labeled as terrorists. They face the risk of assuming a costly juridical process in order to defend themselves from these accusations. Additionally, these attacks break local cohesion and solidarity, something that contributes to the consolidation of these projects.

The neoliberal policy adopted by the government deepens the reprimarization process of the economy. This is partly based on the creation of spaces of sacrifice for transnational companies, without regard to the opinion, projects and desires of the people living in them. The state, in its coercive dimension, is highly present in these spaces.

But big corporations are not the only actors leading this dispossession. In many spaces of the country, mining is being conducted by criminal organizations related to narcotraffic. These groups use hundreds of people, women and children included, to extract gold, silver and copper in extremely precarious conditions. This informal mining takes place without any effective control from the authorities and, on many occasions, it can be understood in symbiosis with corporate mining strategies. The penetration of criminal groups in these activities has reconfigured the grammar of violence that accompanies these conflicts. These criminal groups create the law, control the circulation of value, and dispose of who lives and who dies in the spaces they control. This creates many challenges to local leaders, human rights defenders and social organizations.

The report also shows the living conditions of the impoverished populations in Esmeraldas. It underlines a pattern of violence conducted by the military and the police against the racialized population. The structural racism already present in Ecuador mediates the forms of violence developed by the state, for which black and poor population will always be suspected of crime. Through the report we show the voices of those more affected by this violence.

Finally, the report makes an analysis of the Strategy for the Integrity for Civil Society Organizations (SCOs) and for Non Governmental Organizations (NGOs) recently approved by the government with the assistance of the USAID and Faro. It cast doubts on the real intentions of state authorities behind this Strategy, built without real participation of the OSCs and ONGs affected. It is more than clear that this Strategy has the intention of controlling and of narrowing the margins of action of these organizations, with the ultimate threat of their dissolution. This Strategy has also to be understood within an historical pattern of persecution to these organizations that takes a renewed form in this context.

Under the overall framework of violence that currently marks the country, the work of human rights defenders, activists and social organizations presents many more risks than in the past. Despite their struggle to adapt to these conditions, this labor of monitoring, controlling and denouncing human rights violations conducted by the state and criminal groups is more important and necessary than ever.